Author : A scientific paper written by David Harris, Earth Sciences Department, University College London, London

Read also : Hazard map assessment of Mount Merapi, Central Java, Indonesia using remote sensing

Until very recently, there has been a lack of research into cultural and religious influences upon mitigation responses to natural disasters. There is therefore a need to carry our retrospective investigation of these influences in past natural disasters, and also to understand the extent to which the need for research into these cultural and religious influences is appreciated by current risk mitigation professionals.

To investigate the first aspect, the eruptions of Krakatau in 1883 and Pinatubo in 1991 are compared and contrasted to show how cultural and religious responses have changed over time. The eruptions, although 108 years apart, showed similar trends throughout, for example: syncretic relationships between orthodox religions and traditional beliefs, unique spirits and a large spectrum of actions by the local populace controlled by their cultural and religious beliefs.

To investigate the second aspect, a survey questionnaire was prepared and sent out via the IAVCEI and Volcano ListServ mailing lists. 170 responses were collected. The aim of this survey was to understand how earth and social scientists currently perceive the importance of cultural and religious influences to risk mitigation. The results of the survey showed that a large proportion (88.8%) of the respondents believe that further research is needed and that it is a crucial aspect in education and awareness for local populaces.

It was found that the success of the analytical tools used on both the evidence from Krakatau, Pinatubo and the survey results varied with the aspect being considered. On the one hand, the influence of religion could be understood through content analysis focusing on key words of religious significance. On the other hand, the wide range of terminology used to describe and interpret cultural influences meant that a different approach was needed. Grounded theory was used to identify the roles of key concepts rather than working through specific words.

Future research could involve integrating local communities in the risk mitigation policies as well as using local oral traditions in evacuation procedures, thereby integrating partnerships between the scientific communities and the local populations.

Unless clearly stated otherwise, the data collection, analysis and interpretation present in this dissertation result from my own work alone. I also confirm that this dissertation is within the word limit prescribed for my degree scheme.

1. The importance of culture and religion in volcanic risk reduction

1.1 A Void in Disaster Research

In the past two decades it has become apparent that there is a void in disaster research. Scientific disaster research has made little effort to study and compare cross-cultural experiences, perspectives and perceptions of the affected and threatened peoples in natural disasters (Alexander 1993; Schlehe 1996; Lavigne et al 2008; Chester 2005; Paton et al 2001). Yet, any population affected by a hazard will have its own particular societal and cultural attachments. Therefore, in order to obtain a valid assessment of vulnerability and risk, the ideas and concepts of culture and society must be taken into consideration.

As culture and society affect the vulnerability of a community, it is crucial for risk mitigation that the natural and the social are not separated from each other, as doing so invites a failure to understand the additional burden of natural hazards (Wisner et al 2004). In this thesis, I argue that this void is nowhere more apparent than in looking at how cultural and religious practices shape natural disasters and their responses.

1.2 Defining Culture and Religion

Although various definitions of culture and religion exist within anthropology, sociology and disaster literature (e.g. Peoples and Bailey 2011; Samovar et al 2009; Nanda and Warms 2010), the terms of culture and religion can still be easily misconstrued. The concept of culture can be seen in two lights; one being that culture is an embodiment of a society, changing and placing a reason behind various objects and the other being purely behavioural; placing reason behind actions and motives. For this thesis, the latter definition is used, as motives and actions are crucial for risk mitigation.

Many scholars argue that religion and culture are inextricably interwoven (e.g. Foucault and Carette 1999; Scupin 2008; Kolbl-Ebert 2009). However from the perspective of their effects on disasters, my understanding is that religion differs from culture in that it is a specific aspect within a society, usually generated from historic undercurrents within the culture itself or from places far afield (e.g. Muslims and Mecca). This clear difference between culture and religion emphasises how reactions may differ from person to person and from event to event throughout the world. It is also possible for different cultures to have a shared religion, for example, Christianity and its worldwide influence. The definition which this thesis will use for ‘religion’ will be based upon Banton (2004) and Horton (1960) and is as follows:

The belief in supernatural forces or beings that influences a person’s behaviour and/or understanding of the world around them through certain teachings or tomes. This influence is dependent on where the society and/or person are situated on the religious spectra from orthodox to indigenous and monotheistic to polytheistic.

These two spectra highlight how religion is not strictly one or the other. Societies and individuals have various measures on how strict their religious tendencies are, which influences people to different degrees. Societies and individuals can also hold multiple religions at any one time as well, known as syncretic societies (Chester 2005).

These cultural and religious attachments can become changed and/or affected by a hazard, which modifies a population’s vulnerability. This ‘evolving risk scenario’ (Boyd 1976) is one of the key processes that shape how societies and cultures react to a hazard currently and into the future.

1.3 Cultures, Religions and Volcanic Hazards

Various natural disasters, for example: earthquakes and tsunami can provoke religious and cultural responses. However this thesis focuses on volcanic disasters for several reasons. Volcanoes not only produce various hazards, but eruptions can last days to years (e.g. Mt Etna, Sicily). Another reason is that volcanoes are visually lasting and due to long dormancy times can often create various oral traditions over time.

Volcanic disasters provide notable examples of how cultures and religions shape societies and their risk mitigation strategies (Blong 1984), often referred to as ‘volcano sub-cultures’ (Dove 2008). Volcanic eruptions have the tendency to influence culture, livelihood and reasonings at the local scale. Along with the cultural and religious concepts shaping communities, people’s behaviour and vulnerability, volcanic hazards are also known to be deeply rooted in the socio-economic context and historical development of an area (Chester 1998).

In most cases (e.g.: Mt. Merapi, Mt. Agung and Mt. Vesuvius), human populations who have lived in volcanically active areas for extended periods have oral histories of what can be interpreted as volcanic eruptions (Ort et al 2008). These oral histories can be remembered in legend or can often become incorporated into religious rituals. Transient or migrating populations that live around volcanic regions rarely show such grounded oral histories within their cultures and therefore are likely to be more vulnerable (Ort et al 2008).

Understanding that differences exist between various religions and cultures are critical for developing appropriate means of communicating volcanic risk and encouraging appropriate responses. Hence it is crucial to understand local religions and cultures if responses to natural disasters are to be successful (Chester and Duncan 2007).

Using documentary and historical data of the volcanic eruptions of Krakatau in 1883 and Pinatubo 1991 this thesis will highlight the importance of religion and culture in these past eruptions. Then, using a survey aimed at current earth and social scientists (sent via Volcano ListServ and the International Association of Advanced Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior (IAVCEI) mailing lists) it will examine how religion and culture in volcanic disasters are being perceived currently within the scientific community. Finally it will provide further recommendations on how to use this knowledge for risk mitigation.

2 Previous investigations of cultural and religious responses to volcanic eruptions

2.1 Contrasting culture, religion and oral traditions in volcanic risk reduction

2.1.1 Culture

The dominant, contemporary view of natural hazards is still determined by geophysical and geotechnical perspectives (Hewitt 1983; Chester 1993; Schlehe 2008). Consequently, the complex motivations behind individual and group actions in different cultural settings that led to the original disaster are rarely analyzed and understood (Casimir 2008).

Eleven years ago this void in disaster research was noted by Bankoff (2001). He argued that there has been inadequate attention to considering the historical roots of which ‘risk’ is generally presented. This was the first of many attempts to portray culture in the light of disasters and although much of a culture and its religion rests upon that regions history, Bankoff (2001)’s approach still does not fully complete the picture of culture and religion entirely. If the human factor in natural disasters is fully understood in terms of their reactions, their history or their perceptions, then analysis of cultural and religious responses to volcanic eruptions can start.

Unfortunately a community does not simply contain one set of scenarios, perspectives or vulnerabilities for any one event or hazard. This is due to various factors such as: age, experience, gender, social status or religious beliefs changing the way people behave in certain scenarios. In doing so, any size community will contain such a variety of vulnerabilities, perspectives and beliefs that it is possible, in some places, that each person can have their own advantages and disadvantages in different scenarios and natural hazard events.

This generates a diverse vulnerability within a known region; with a general rule that the larger the region measured the more diverse the vulnerability can be to different hazards. Vulnerability can be assessed on many different factors: economic, social, demographic, political and psychological and therefore is too complicated to be captured by models, frameworks and numbers (Twigg 2001). It is also recognised that the impact of culture and its response to natural disasters varies wildly; from cultural collapse, through fragmentation of society, dramatic changes, and development of new technologies, to little apparent change (Ort et al 2008; Grattan and Torrence 2010). This is why understanding deep-rooted local culture should be considered crucially important if responses to disasters are to be successful (Chester 2005).

Many researchers (e.g. geologists and volcanologists) doubt the importance of culture during an emergency, potentially as there are too many factors to quantify (Twigg 2001). Although, previous examples and their death tolls in the last two decades, for example: Mt. Merapi 2010 (Donovan and Suharyanto 2011; Harris 2012) and Mt. Pinatubo 1991 (Punongbayan and Newhall 1996), show that for effective disaster management, culture should not be considered as ignorance, superstition or backwardness (Chester 2005), and that the potential importance of traditional knowledges is often forgotten (McAdoo et al 2008).

2.1.2 Religion

Religious links to volcanism is still a debated topic. Elson et al (2002) describes the link in a somewhat lyrical fashion:

“[Volcanoes] are fire-breathing, earth-shaking creatures, who, accompanied by lightning and thunder, have the power to turn day into night… It is little wonder that ritual and volcanism go hand in hand.”

Bearing in mind that over 1,500 volcanoes have been active in the Holocene worldwide (Small and Naumann 2001), it may come as a surprise that symbolism is not rife in a global context but as Hanska (2002) states:

“The last redoubts of religious explanations of disasters are either found in extreme biblical-literalist Christian circles within MEDC’s, or in those societies within LEDC’s which are relatively untouched by the forces of modernism.”

Hanska (2002) assumes that the extreme Christian circle is the only religion that concentrates on natural disasters and the impact on its people within More Economically Developed Countries (MEDC’s). This is wrong, and is an ongoing mistake made by major treaties and previous disaster reports.

In fact, some major studies have overlooked religion in their assessment of the works in the field (Burton et al 1993; Drabek 1986; Lewis 1999), assuming it to be irrelevant in MEDC’s. However, even in the most recent warnings of an eruption of Popocatepetl, Mexico in April 2012 (a rapidly modernising country), only half of the population surrounding the volcano agreed to evacuate; with a local resident stating: “Two days ago when the volcano wanted to throw fire. Church Bells started to toll, calling people to pray… and that’s how we get the volcano to calm down” (BBC 2012). This adds to the argument against Hanska (2002). Eruptions of Mt. Etna are also a prime example to use against Hanska (2002)’s statement. Sicily is a well developed nation and yet on occasion after occasion the nearby priests and people parade relics when large eruptions occur, for example in 2001 (Chester et al 2008).

In risk mitigation practices, religion is widely perceived as bad behaviour, for example: praying or processions puts more people at risk. While this is true for some disasters, for example: Mt Merapi in 2010 (Donovan and Suharyanto 2011) and Mt Agung in 1963 (Jennings 1969). Chester et al (2008) showed that around Vesuvius and Etna religious practice does not seem to obstruct other types of protective behaviour but are simply one of the protective behaviours used by people before, during and after volcanic emergencies. In fact, religious or cultural mechanisms for coping with a natural disaster, such as volcanic eruptions, are highly adaptive, enabling affected individuals and groups to more readily accept the event and begin the recovery process (Nolan 1979), for example: Christian circles helping with recovery in Pinatubo and exchange networks occurring in Papua New Guinea (Chester and Duncan 2010).

Much like ‘culture’, religion can therefore never be detached from the larger picture of risk mitigation, as it always interacts with the social, economic and political constraints in the construction of a population’s vulnerability in the face of natural hazards (Gaillard and Texier 2010).

The paradigm in disaster research on religion and natural disasters is tainted by three short comings. Firstly, there is a failure to consider the diversity of religious beliefs throughout the world and instead are focused on the Judeo-Christian concept. Secondly, and a slight development from the first statement, the religion and natural disaster paradigm is viewed almost as ignorance or backwardness. Thirdly, the paradigm is shown in a light that assumes vulnerability and mitigation as a simple model of efficient and sustainable risk reduction based on policies developed in Western countries. Yet, places matter and religions are always embedded in local cultural beliefs (Gaillard and Texier 2010).

On the other hand, in the last decade scientists and social scientists have been increasingly trying to work together. Social scientists have engineered partnerships with many communities worldwide within disaster risk reduction and have discovered that communities living around disaster areas have certain indigenous knowledges about disasters, which are either built on experiences, stories throughout generations or via art. These knowledges are called oral traditions.

2.1.3 Oral Traditions

Oral traditions are a major faculty of culture that comes from living close to a certain landscape, they are often shaped and built on various stories from the land; either about the creation of a mountain, a previous event or even a possible future event. Oral histories of volcanic eruptions become integrated into societies and communities surrounding a volcano either through depiction in art, remembered via legend, or most often by becoming incorporated into religious rituals (Ort et al 2008).

It is not uncommon for various forms of communication, such as stories, songs, rituals or paintings to be created during a natural disaster; oral traditions are one such creation. Although shaped by compression, stylisation and time, given their nature of transmission through generations (Barber and Barber 2004), these oral traditions may be constructed, in part, to insure the adaptation of a society to the environment (Minc 1986), including mitigation of local volcanic hazards (Cashman and Cronin 2008) and disaster recovery (Shanklin 2007).

Sources of this nature can be used to gain otherwise unavailable perspectives, not only on the workings of the cultures of non-literate peoples but also on events of significance in their past (Moodie et al 1992). Yet this seems to have been neglected in more recent times as Cashman and Cronin (2010) claim;

To date, these oral traditions or stories have been largely neglected in modern volcanic hazard mitigation, that is, in helping local communities to make themselves more resistant to volcanic hazards posed by their environment.

It would seem there has been a break, or rather, a failure in communication since Moodie et al (1992)’s statement. The International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction (IDNDR) was designated for 1990 to 2000 and was sought to mediate and reduce risk on all types of natural disasters. A list of ‘Decade Volcanoes’ was created which contains the volcanoes that were considered to be the ‘most-at-risk’. The strategy had the promise to continue with further work and research into the 2000’s and 2010’s from the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UN-ISDR) and yet it has fallen on the way side over the last decade. One particular reason may be that large eruptive activity has been benign in the last decade or so, compared to that of the 1980’s and the early 1990’s.

The time frame of satellite and instrumental recording is possibly the main reason for why it requires more work, but the idea of oral traditions acts as a from of a palaeohazard, reconstructing events from historical documentation or legend. Much like with geological evidence generating the history of an event from looking at rocks. This palaeohazard concept should not be discarded from studies. Consequently, in the ages of instrumentation and remote sensing, eye-witness observations of scientists and non-experts are still vital to fully understanding eruptive sequences and processes (Cashman and Cronin 2008).

So far, this thesis has given a very broad brush over why the importance of culture and religion should be considered within risk reduction from the perspectives of Hewitt (1983), Chester (1993; 2005), Cashman and Cronin (2008; 2010), etc. In the following chapters, specific case studies of major examples in the past 100 years are examined and highlight in detail how culture and religion has shaped people’s perceptions, the disaster impact and also disaster recoveries and how it is perceived currently.

2.2 Past influences of religion and culture in volcanic environments and eruptions

2.2.1 Holy Texts and Natural Disasters

In many teachings of religions, the idea of natural disasters plays a major role; either as an act of God, a form of retribution or sometimes a consequence of sin for non-believers. The most well known examples of this idea are found within the holy texts of Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Hinduism.

With Buddhism however, volcanism itself is not mentioned, but the cause of earthquakes can be seen when a Buddha leaves to Nirvana (Metha 1988). Sikhism is different again as it is a form of a religion and a philosophy, not mentioning volcanism but whereby the ‘Lord controls everything and humans are destroying everything’ (Hughes 2005).

Another religion that sees natural disasters differently is Shintoism. Shintoists are at the mercy of nature, but also protected by nature. Nature does not consider humans to be the most important thing; the kami (the spirits) are the most important. In Shintoism, people are here by the grace of gods, but are not their main concern. Natural disasters occur because this is just how nature is.

A well known example can be seen in the most recognised and Western-dominated religion: Christianity. In the Old Testament of the Bible (Genesis 19:23-24) two cities, Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed by fire and brimstone:

“Then the Lord rained upon Sodom and upon Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven” (Genesis 19:24, King James Version)

Another example is from the Koran, the holy text of Islam. Throughout this holy text there are multiple mentions of Allah acting on the unjust, for example:

“And We turned the cities upside down, and rained down on them brimstones hard as baked clay.” (15: 74 – 75, Surat Al-Ĥijr)

This latter quote refers to a volcanic eruption on Sodom and Gomorrah after they rejected Allah’s warnings and so tornadoes and volcanic eruptions soon ensued. Islam and Christianity have overlaps in their teachings as they have both have common roots in Judaism, where this myth of Sodom and Gomorrah originates.

From the examples of Christianity and Islam it is clear that volcanic eruptions, or natural disasters, are seen as a response to spiritual transgressions or teachings, and offerings are usually made in an attempt to remediate these ‘sins’ and avert ongoing destruction (Scarth 1999). This effect is also evident in small religious and cultural circles surrounding various volcanoes, for example: Mt. Merapi (Dove 2008; Donovan 2010; Donovan and Suyarhanto 2011), Mt. Agung (Jennings 1969) and Mt. Pinatubo (Gaillard 2007; 2008).

It is often believed though that the last redoubts of religious explanations of disasters are in those societies which are untouched by modernism (Hanska 2002). Assuming this to be the main reason why various risk strategies and policies do not include religion and culture; this thesis shall now concentrate on the last century of examples of religious and cultural responses to disasters, rather than focus on old teachings from holy texts.

2.2.2 A Century of Responses

A recent trend towards the involvement of social scientists in the investigation of responses to natural disasters has led to the analysis of accounts of volcanic eruptions during the 20th century in particular.

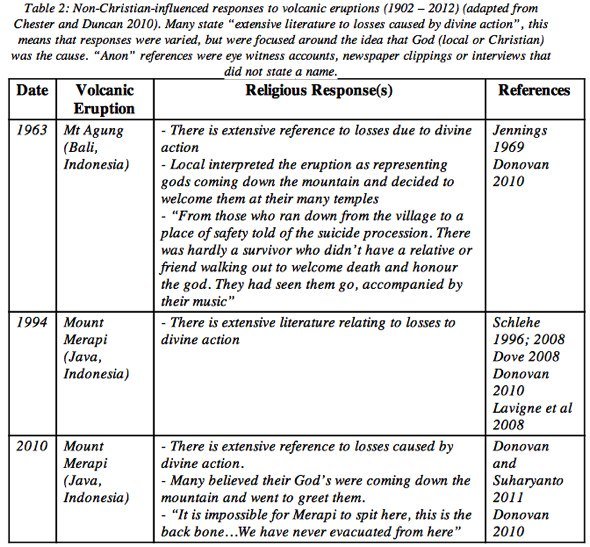

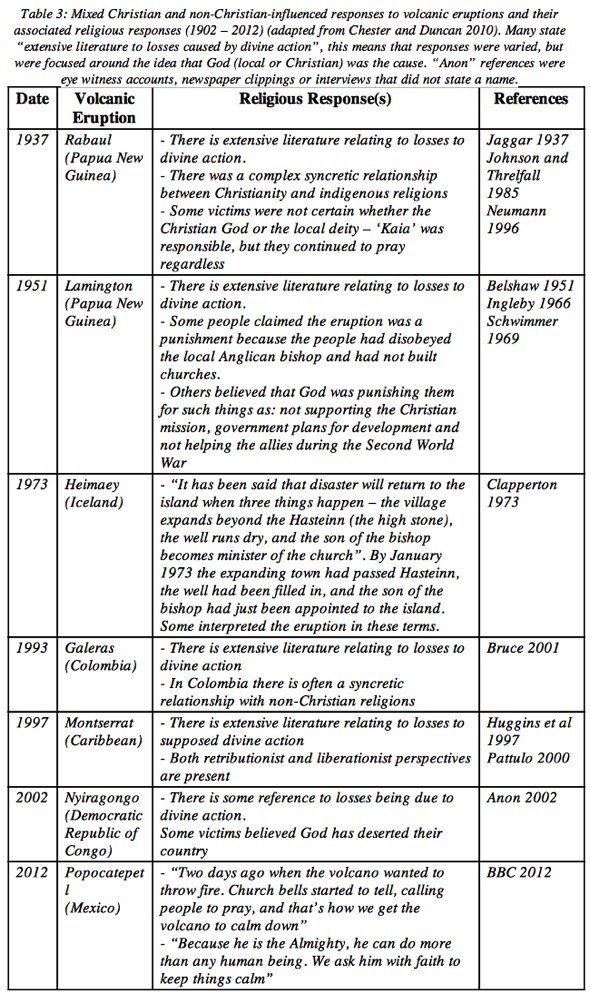

Religious responses to natural hazards can be labelled more easily than an unclear ‘cultural’ response over time. For this reason tables 1, 2 and 3 show various volcanic eruptions and their summarised religious responses only (from 1902 – 2012) (Krakatau 1883 and Pinatubo 1991 are omitted as they will covered in greater detail later in this thesis):

Hanska (2002) states that ‘religious responses to volcanic eruptions are not apparent in recent times’, yet the eruptions of Nyiragongo (2002) Mount Merapi (2010) and Popocatepetl (2012) all happened in the last 10 years, highlighting that this is still an important topic of discussion within disaster literature.

2.3 Coding Qualitative Data

Due to the nature of social science research, this thesis will rely upon qualitative data such as eye-witness accounts, other contemporary documents and responses to a questionnaire based survey. This requires different analytic methods compared to physical science due to subjectivity and opinion. The methods that this thesis will use are content analysis (Section 2.3.1) and grounded theory approach (Section 2.3.2).

2.3.1 Content Analysis

Content analysis is a very basic method. The method consists of picking out particular words or phrases from the source documents (e.g. eye-witness accounts, magazines and newspaper clippings) that corresponds to a particular theme.

This method has been chosen for qualitative analysis on religious accounts (Sections 4.3.1 and 5.2.1) as it provides an approach that can easily pick out key words from texts.

2.3.2 Grounded Theory Approach

Grounded theory approach will be used to analyse the cultural and survey responses (Sections 4.3.2, 5.2.1 and 7.3.3). The main reason for using Grounded Theory is that it provides an easy understanding of codes and themes when looking at qualitative data and so analysis becomes simpler and more rigorous.

Methodology and analysis of grounded theory are constantly revised and proceed in tandem (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Thus, two central features of grounded theory approach are that it is concerned with the development of theory out of data and that the approach is iterative, meaning that data collection and analysis proceed in tandem (Bryman 2008).

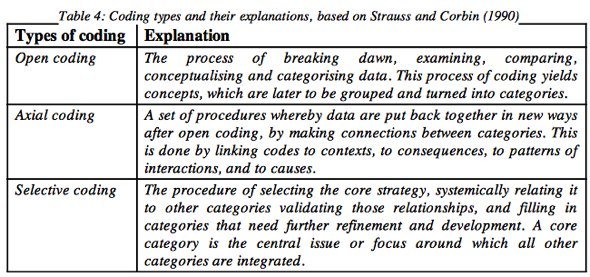

Within grounded theory there are multiple ways of analysing data, one of which is ‘coding’. Coding is a key process in grounded theory, whereby data is broken down into parts, which are then given names. Coding begins soon after the collection of initial data, and unlike quantitative research that requires data to fit into pre-conceived standardised codes, a researcher’s interpretations of data shape his or her emergent codes in grounded theory (Denzin and Lincoln 2003). The codes can serve as devices to either; label, separate, compile and/or organise data (Denzin and Lincoln 2003). Coding in qualitative data analysis also tends to be in a constant state of revision and fluidity (Bryman 2008). This means it is an iterative process and requires multiple returns to the data to ensure that all of the source documents are examined using the same coding.

Within the social science literature three types of coding exist; ‘open coding’, ‘axial coding’ and ‘selective coding’ (table 4):

The thesis will now concentrate on two examples of historic eruptions; Krakatau in 1883 (Section 4) and Pinatubo in 1991 (Section 5) and show in detail the cultural and religious responses that occurred there and their influence on risk mitigation.

3 Questions to be Addressed

Considering the examples so far in this thesis; for example tables 1, 2 and 3, several questions are highlighted:

- How have religious and cultural responses changed over time?

- Considering the examples given, how do earth and social scientists perceive cultural and religious responses to disasters?

- How do scientists’ perceptions affect risk mitigation strategies they put forward?

- What practices exist for integrating religious and cultural responses into risk mitigation?

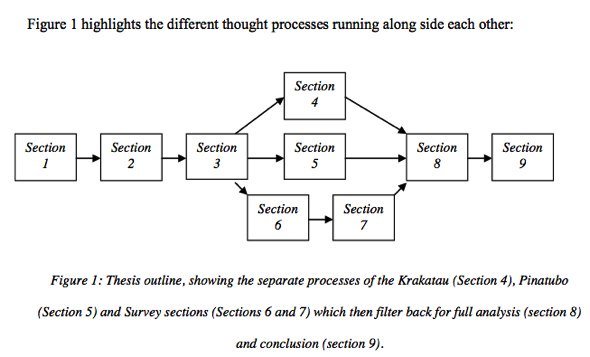

To answer these questions this thesis will be split into three separate sections:

- Sections 4 and 5: Comparing and contrasting the cultural and religious responses of the volcanic disasters of Krakatau in 1883 and Pinatubo in 1991 to show how people were affected by two eruptions 108 years apart and how responses have changed.

- Sections 6 and 7: Analyzing a survey completed by 170 people (a mixture of earth scientists and social scientists) to see how religious and cultural responses are perceived currently within the scientific community.

- Sections 8 and 9: Combining sections 1 and 2 to find inter-comparisons and contradictions between the secondary research (1) and the primary research (2) collected, and to recommend a solution on how to include religious and cultural responses in volcanic risk mitigation in the future.

3.1 Different cultural and religious responses from two historical examples

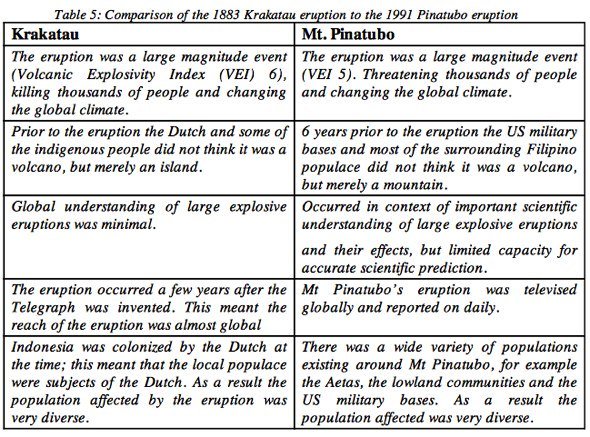

There are various reasons why the eruptions of Krakatau in 1883 and Pinatubo in 1991 have been chosen as illustrative case studies (table 5):

The eruptions share multiple similarities, but also show important differences. The key difference is that they were 108 years apart and occurred in very different social, political and scientific contexts.

On the other hand, many similarities are shared between Indonesia and the Philippines, for example; past colonial rule, large proportions of the populations living below the poverty line and large numbers of active volcanoes. These similarities above and in table 5 provide a good foundation to critically compare and contrast the two countries and the impact that the eruptions caused.

4 Krakatau 1883 Documentary and Archival Evidence

4.1 Krakatau 1883

4.1.1 The Eruption

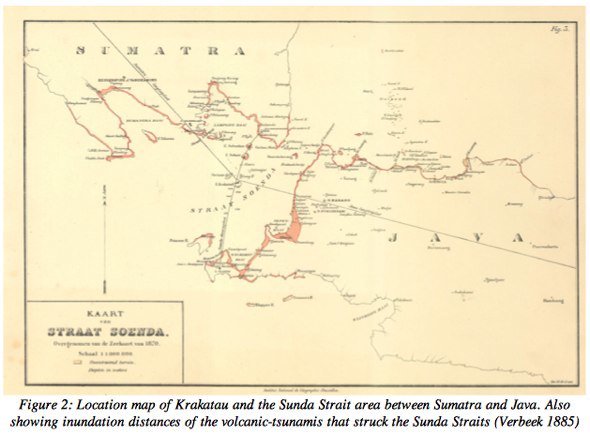

Krakatau (often misspelt as Krakatoa or Cracketouw), is located in the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra in Indonesia (figure 2). Krakatau was the first major eruption to occur after the development of the telegraph, and, as such made a vivid impression over much of the world almost immediately (Self 1992). Death toll estimates range between 35,000 and 100,000 people (Besant 1883; Simon 1983; Winchester 2004; Camp 2006).

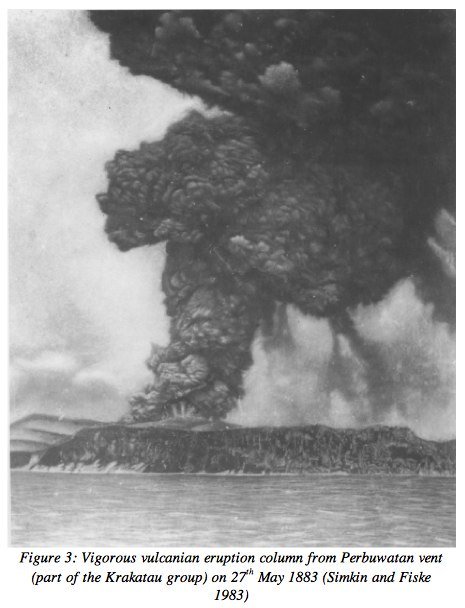

The 1883 eruption lasted four months in total but the climactic phases were confined to one 24 hour period on the 26th and 27th August during which over 90% of the erupted material was released (Self 1992). Prior to this climactic episode in August, minor eruptive activity begun on 20th May 1883 beginning with emission of fine-ash and pumice (Self 1992) (Figure 3). Reports indicate that residents in Batavia (now Jakarta) were bemused by this activity and day trips in steam boats began to see the spectacle (Ball 1888).

For the next two to three weeks the intensity of the eruptive phenomena seemed at first to decline (Self 1992), but by June other craters began to open on the island, and the volcanic energy steadily increased until 10:00 on 26th August (Ball 1888), with the atmosphere being described as “hot, choking and sulphurous” (Anon 1885).

The climactic eruption column was estimated to be 26km high, covering nearby islands with several feet of ash (Simon 1983). At 17:00 that same day the first widespread tsunamis were recorded (Simon 1983; Camp 2006).

Between 5:00 and 11:00 on the 27th August large pyroclastic flows were emitted from the volcano (Self 1992). Several pyroclastic flows travelled 40km across open water and reached the Southern shore of Sumatra killing 2,000 people around Lampong bay (Simkin and Fiske 1983). The greatest tsunami occurred on the 27th, cresting approximately 120ft high, erasing all trace of whole towns, including Telok Betong, Merak and Tyringin (Simon 1983; Sigurdsson et al 1991; Verbeek 1885). The sounds of the eruption during this period reached up to 3,000 miles away in the island of Rodriguez, where it sounded like “heavy gun fire” (Paul 1884).

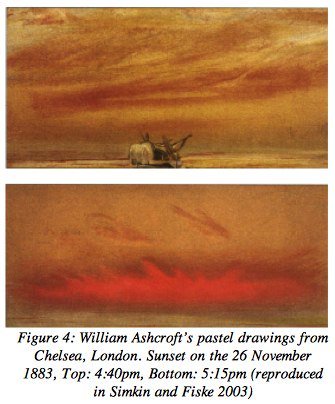

The resulting volcanic particles travelled into the stratosphere and gradually travelled around the Earth, causing speculation and bemusement in nearly every city, as it was changing the colour of the sky and the sun (See figure 4):

This dispersion of Krakatau’s volcanic particles later influenced the discovery of the atmospheric circulation system, influenced Edvard Munch’s Scream (Olson et al 2007) as well as changing the Earth’s global climate for several years.

4.1.2 Records of the Responses to the Eruption

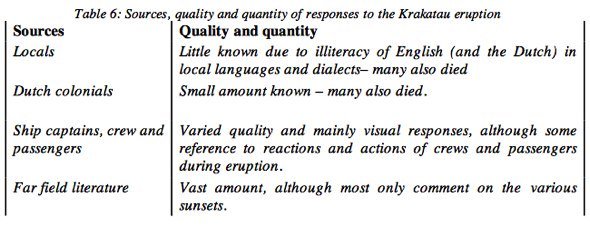

Due to the hierarchical population existing in Java and Sumatra at the time, much of the evidence that was reported of the eruption was written from a scientific perspective and ignoring the Javanese culture, as well as from the far field (table 6). There was no systematic study of the religious and cultural responses to the eruption made at the time either. However, due to a large amount of research from Simkin and Fiske (1983) and various primary research investigations, the following chapter (Section 4.2) will focus on how the eruption of Krakatau was interpreted, either as a religious or cultural response from eye-witness accounts, magazine or newspaper clippings. This is followed by Section 4.3, which analyses the accounts found during the eruption of Krakatau and investigates common themes that run throughout.

4.2 Krakatau Methodology

4.2.1 Krakatau Religious Responses

To classify a religious response to an eruption is particularly difficult considering the definition of religion (Section 1). As Indonesia was under control of the Dutch at the time, the mixture of beliefs varied extremely. The Dutch held tight Christian beliefs, whereas the local people were syncretic, holding Muslim beliefs mixed in with local traditions.

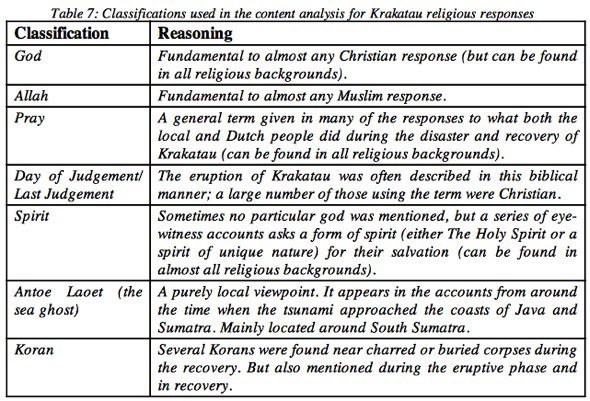

The methodology used in this section is ‘content analysis’ (Section 2.2.3.1); the words used to classify a response in a religious context are shown in table 7:

This list reflects the mix of Christian, Muslim and traditional Indonesian beliefs that were found during the investigation of religious responses.

The data can be found in Appendix 1: 1.1.

4.2.2 Krakatau Cultural Responses

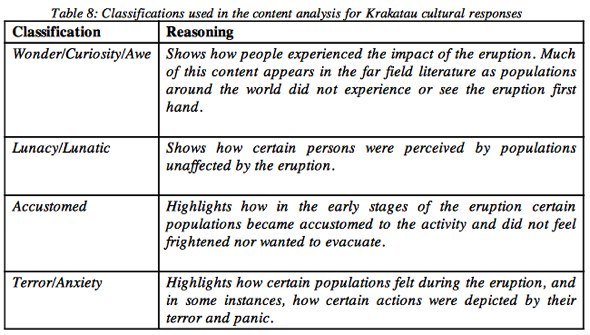

A similar content analysis from Section 4.2.1 was completed for cultural responses to the Krakatau eruption (table 8):

This list reflects the mixture of emotions, motives, actions and responses that were found during the investigation of cultural responses.

The data can be seen in Appendix 1: 1.2.

4.3 Analysis of Krakatau 1883 data

4.3.1 Critique of the Methodology

This methodology is not without its drawbacks. The content analysis technique for the Krakatau religious and cultural responses presented some problems, especially in respect of the content analysis of cultural responses (Section 4.2.2).

Section 4.2.2 provided an interesting example on how content analysis can fail in social science. Section 4.2.2 showed cultural characteristics, and as highlighted in Section 1, culture can vary from a large array of different behavioural actions. The unclear spectrum that ‘culture’ entails thus results in an imprecise method if using purely singular phrases or words.

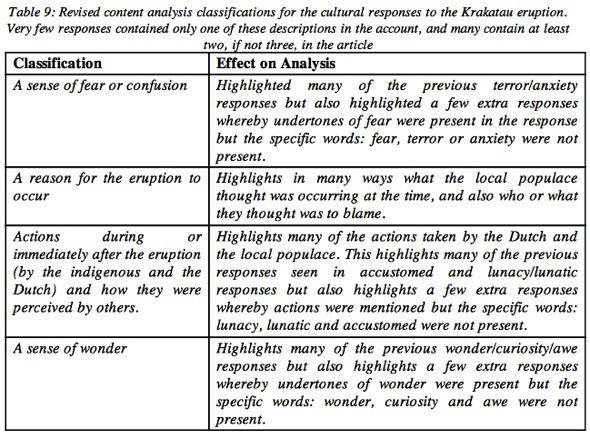

For this reason a new analysis was undertaken. Instead of picking out individual and specific words or phrases from a response, the basis changed to grounded theory approach (Section 2.3.2) (table 9).

The data can be found in Appendix 1: 1.3

Section 4.2.1 however worked well. The distinction between religions and cultures is that in religions (especially orthodox religions), precise wordings used either by the populace there or written down in texts are familiar worldwide, for example: God and Allah. The chosen list of words and phrases therefore provided a good foundation or what classified as a religious response.

4.3.2 Author and Theme Analysis

When investigating the methodology of Krakatau it is important to note the profession of the author/eye witness and theme of the article (e.g. newspapers, magazine articles and eye witness accounts). This is a significant factor as it provides the background of the author/eye witness and what is trying to be said by the piece and can provide a bias, such as: focusing on one part of the eruption over another.

In the interest of the Krakatau eruption, this is an important aspect of the response as many of the far field literatures were responding to the Krakatau eruption as a form of communicating a disaster report from a scientific basis and thus making the themes of the articles purely scientific discovery rather than a disaster report in the contemporary sense.

The author’s name of the articles also became an issue as unfortunately many of the newspaper reports gathered from the late 19th century did not state the authors name in the print. Also around the time of the late 1800’s those with religious appointments were seen as trusted individuals and where seen as a means for providing scientific discoveries or interest, for example: Charles Darwin. This resulted in many of the Krakatau responses being written by people of the clergy. Yet, religion was not mentioned; instead many reverends actually wrote the articles as a form of interest and to educate the public, such as writing in Gentlemen’s Magazine or Leisure Hour.

4.3.3 Response Analysis

A major trend that runs throughout both religious and cultural responses is the idea that the eruption was highly unanticipated. Also, much of the far field literature for not actually seeing the eruption had a general feeling of unease about the eruption, especially the sunsets, for example:

- Anon (1891): “The people could not imagine whence it came, nor judge it to be anything else but an effect of a general destruction of the world”.

- Anon (1888): “The gorgeous sunsets of November 1883 were the subject of common conversation and wonder”.

- Williams (1884): “Accounts of extraordinary sunsets have flowed in from all parts of the world…superstitious terrors and intelligent curiosities have been simultaneously awakened by these unnatural manifestations of sunlight”.

Whereas the major trend that ran throughout the responses of those in Sumatra and Java who had experienced the eruption first hand had mainly Biblical or Muslim/local belief undertones, for example:

- Capt. Sampson’s diary cited in Johnson (2004): “A fearful explosion. A frightful sound…I am convinced the day of Judgement has come”

- Tenison-Woods (1884) cited in Simkin and Fiske (1983): “No human tongue could tell what happened. I think Hell is the only word applicable to what we saw and went through”

- Mrs. Beyenrick’s diary cited in Simkin and Fiske (1983): “Around the hut lay thousands of terrified natives, moaning, crying and praying to Allah for deliverance”.

- Furneaux (1965): “From Java and Sumatra rose a great cry of fear. The distraught people turned to their gods for aid. ‘Allah il Allah’, prayed the Muslims. ‘Lord, deliver us’, beseeched the Christians”

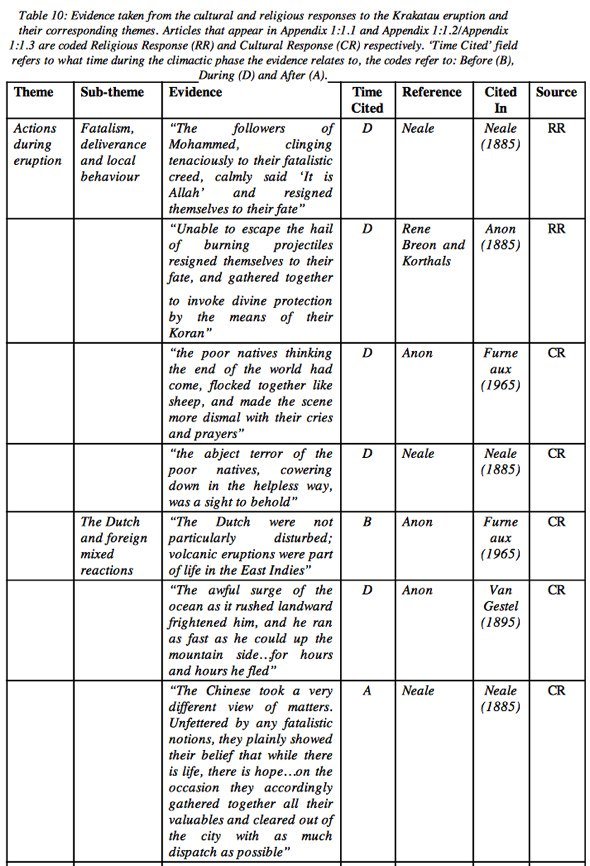

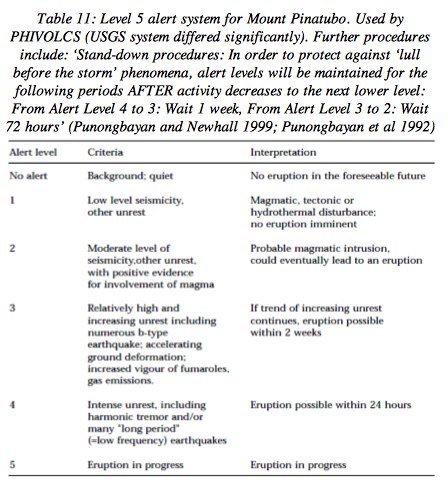

Examining both religious and cultural responses, there were three main trends that occurred throughout both sets of responses (table 10):

Note: Atjeh, Achitenese and Archimase mentioned in Furneaux (1965) and Simkin and Fiske (1983) respectively are different spellings of modern Aceh.

From these above actions it seems that the local populace had not anticipated such a large eruption to occur, for example: “abject terror of the poor natives”, and in some respects acted in a fatalistic attitude; “unable to escape the hail of burning projectiles resigned themselves to their fate, and gathered together to invoke divine protection by the means of their Koran”. Whereas the foreigners and colonials seemed to know the best action to take; “The Europeans also thought it wiser to suspend business on account of the darkness and to leave the city for their suburban homes”. This is possibly because they had a choice to evacuate or they had read about previous volcanic eruptions. However, it can also be argued that the actions of the sea captains and the foreigners come from their different cultural ‘orientation’ (Boyd 1976) and belief in efficacy of action.

On the other hand, the volcanic islands of Java and Sumatra have had large amounts of volcanic eruptions throughout the last two centuries, and thus potentially local people gained experience on volcanic eruptions. However, the difference is that the Western world analyzed these eruptions whereas the Indonesians did not and reacted passively, rather than proactively.

However, the interesting facet of table 10 however comes from the different religions that the local people held. Both Muslim beliefs but also the traditional beliefs are apparent, for example: the Koran on one hand and the mountain and sea ghosts on the other. The concept of the sea ghost that occurs in Mrs Beyenrick’s diary could stem from the local people witnessing previous tsunamis that struck the Sumatra coastline (most recently in 1797 and 1833) and then from that, oral traditions may have been generated.

Another facet that arose after the disaster was the idea of blame. This is linked very closely to ‘cause of the eruption’, but having it as a separate section highlights the more cultural aspects that were present in Indonesia at the time. The animosity and blame mentioned in table 10 highlights how the local people felt towards the Dutch which occurred from the hierarchical relationship that was present at the time, especially the role of oppression of Aceh mentioned in various accounts.

An interesting theme to pull from within table 10 is the idea of syncretic relationships within the local populace, especially from Furneaux (1965) and Neale (1885). Although the citations mention the unique spirits (for example the mountain and sea ghosts) the local populace’s actions are actually very much Muslim practices; thus highlighting that two ideologies exist within the communities there: one acting as the cause, the other one for the effect.

Although these three main trends are significant findings during the investigation of the eruption of Krakatau in 1883, there is still a large void in this thesis on what has happened since and how these findings found here have changed or been recognised within volcanic risk mitigation. The next section shall look at the eruption of Pinatubo in 1991, and assess how responses of religion and culture have changed over a period of 108 years in a socially similar part of the world.

5 Pinatubo 1991 documentary and archival evidence

5.1 Pinatubo 1991

5.1.1 The Eruption

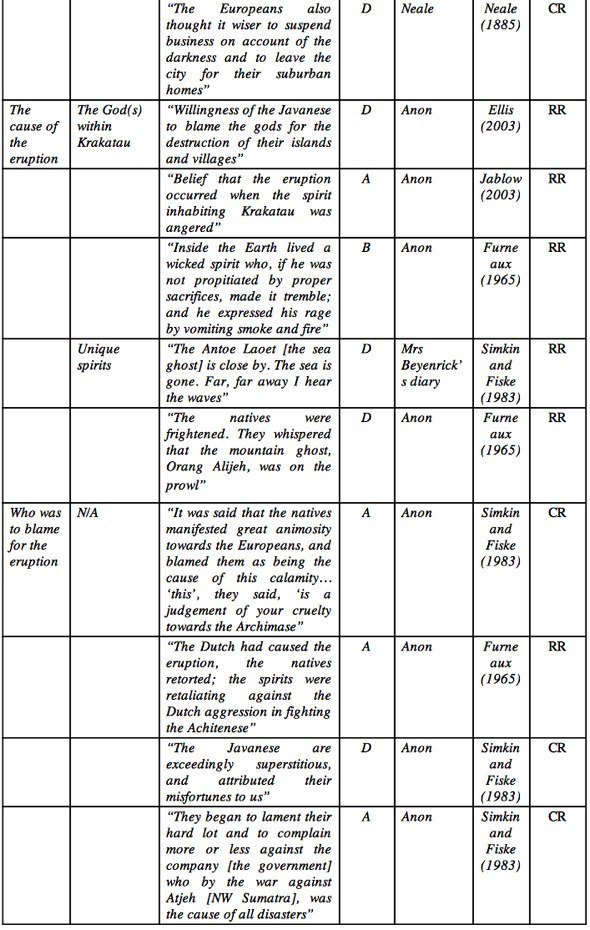

Mount Pinatubo is located on Luzon Island in the Philippines (Punongbayan et al 1992) (figure 5) and was the site of the largest volcanic eruption of the 20th Century (Gaillard et al 1999; Leone and Gaillard 1999).

Prior to the main eruptive phase on 12th – 15th June 1991 more than 30,000 people lived in the small villages on the volcano’s flanks, with around 500,000 living in cities and villages on the areas surrounding the volcano (Wolfe and Hoblitt 1996; Thompson 2000).

The last eruption occurred 460 – 600 years before 1991 (Punongbayan and Newhall 1999), and so most of the local population believed it to be a mountain and not a volcano. However, some of the local populations, the Aetas, did have oral traditions containing descriptions about Pinatubo and their god; Apo Namalyari, who hid within the volcano (Gaillard 2006; Seitz 1998; Punongbayan and Newhall 1999).

Volcanic unrest on Pinatubo began as early as the 3rd August 1990. This consisted of minor fumarole activity, rumbling sounds, ground cracks and landslides (Punongbayan et al 1996).

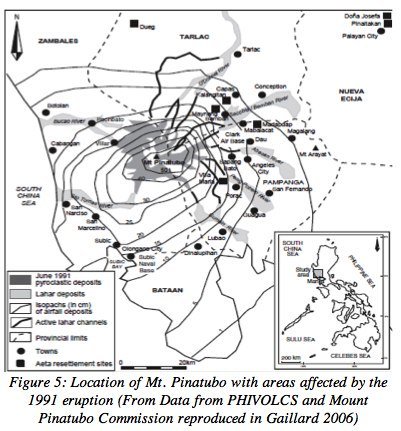

When eruptive activity began from 2nd April 1991 the local volcanic observatory (the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS)) started to recommend evacuation procedures, starting with a 10km evacuation zone on 7th April 1991 (Gaillard 2007; Thompson 2000). A 5-level alert system was then adopted on 13th May 1991, with level 2 being adopted on the same day (table 11):

By June 5th 1991, Level 3 Alert was raised and around this time ~10,000 Aetas started to evacuate in response to PHIVOLCS evacuation measures (Punongbayan et al 1992). Two days later on June 7th, earthquake occurrence inflated from 1,000 events to 2,000 per day and an ash explosion that reached 8km made PHIVOLCS increase the Alert Level to 4 (Punongbayan et al 1992).

On 9th June 1991 Level 5 Alert was given after a large pyroclastic flow was sighted in the Zambales region. An immediate 20km evacuation radius was given. Within a day 25,000 inhabitants (mostly Aeta’s) had evacuated and 14,500 US personnel were evacuated from Clark Air Base in response to the United States Air Force General’s order based on USGS advice (Punongbayan and Newhall 1999).

From 12th to the 15th June 1991, Pinatubo erupted with large explosive eruptions producing large ash falls, pyroclastic flows, lahars and cooled the global average temperature by -0.6°C (Casadevall et al 1996) , forcing the evacuation zone radius to be increased to 30km on the 14th then to 40km on the 15th (table 12).

The increase in evacuation zone radii encompassed previously regarded safe zones and caused scepticism, especially to the Mayor of Olongapo City to the South, whose area was previously regarded as safe (Punongbayan and Newhall 1996). After the eruption, most of the death toll occurred at Olongapo City due to wetted ash fall and roof collapse and not from the pyroclastic flows. This was possibly due to unanticipated impact of typhoon Yunya that followed shortly after the eruption that wetted ash further and made it especially heavy. By the end of the eruptive activity about 180 people were killed, mostly by roof collapse, with another 50 to 100 deaths caused by the pyroclastic flows and the initial lahars (Punongbayan et al 1996).

5.1.2 Records of the Responses to the Eruption

Unlike Krakatau, much of the responses to Pinatubo were easily accessible, the eruption itself has been studied heavily and so the quantity of responses was very large. Also due to the response teams from PHIVOLCS and USGS (especially their pre-climactic phase education programme) first hand knowledge, responses and actions were recorded. Add to this the compilation of major works by Punongbayan and Newhall (1996). Availability of data was very high.

The following chapter (Section 5.2) will focus on how the eruption of Pinatubo was interpreted, either as a religious response or cultural response from eye-witness accounts, magazine and newspaper clippings or journals. This is followed by Section 5.3, which analyses the accounts found during the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo and investigates common themes that run throughout.

5.2 Pinatubo Methodology

5.2.1 Pinatubo Religious Responses

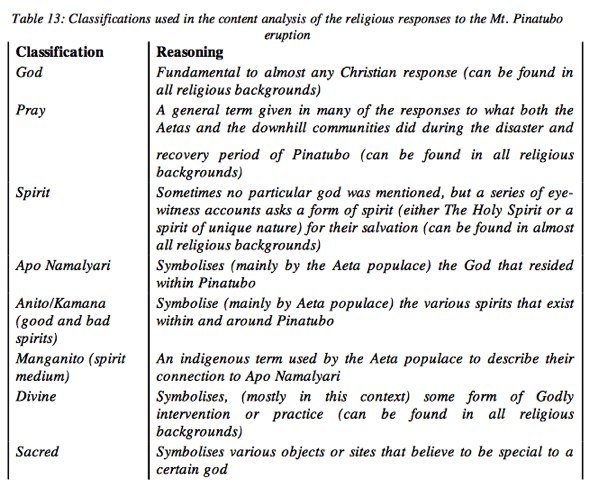

Considering the positive outcome of using content analysis on the Krakatau religious responses (Section 4.2.1) this section will use the same methodology with a similar classification (table 13):

Some similarities maybe found in Section 4.2.1, for example: god, pray and spirit, however this list reflects the mix of Christian and local beliefs that existed around Mount Pinatubo at the time. The differences from Section 4.2.1 however are mainly from the different syncretic relationships that exist around Pinatubo compared to that of Krakatau.

The data can be seen in Appendix 2:2.1.

5.2.2 Pinatubo Cultural Responses

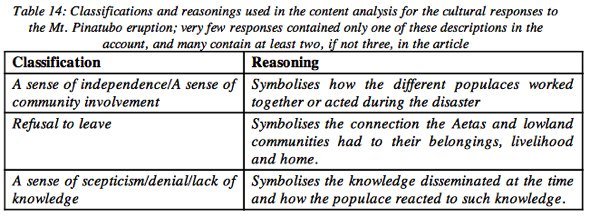

Considering the negative outcome from Section 4.2.2, a grounded theory methodology (Section 2.3.2) will be used (table 14):

The largest difference from Pinatubo responses to Krakatau’s responses is the latter section; “A sense of scepticism/denial/lack of knowledge”. This is evident in Pinatubo responses as it mainly in reaction to from the PHIVOLCS and USGS education campaigns that were sent out to the local communities.

The data can be seen in Appendix 2:2.2.

5.3 Analysis of Pinatubo 1991 Data

5.3.1 Author and Theme Analysis

Similar to Section 4.3.2, the author and theme of the account is important for document investigation, especially concerning the aspect of bias. With regards to the Pinatubo eruption, a large amount of work completed on the human populations that were at risk was completed by social scientists, thereby giving an emphasis on the actions and responses of the people at the time. Also, at Pinatubo not only was there a connection between the indigenous populations, the Aetas, and the nearby communities but there was also a partnership made between the local government, PHIVOLCS and the USGS.

5.3.2 Response Analysis

As a comparison to Krakatau, the Pinatubo eruption was reported globally and throughout its eruptive process. Krakatau however, was only reported on when the climactic phase occurred. This difference generated a very diverse set of responses compared to Krakatau. The different stages; varying unrest, knowledge dissemination and variations in evacuation orders and radii; each came with their own set of responses depending on the populace affected. This variety generated a wealth of information on how populations respond to natural disasters in the Philippines and how current risk mitigation strategies work.

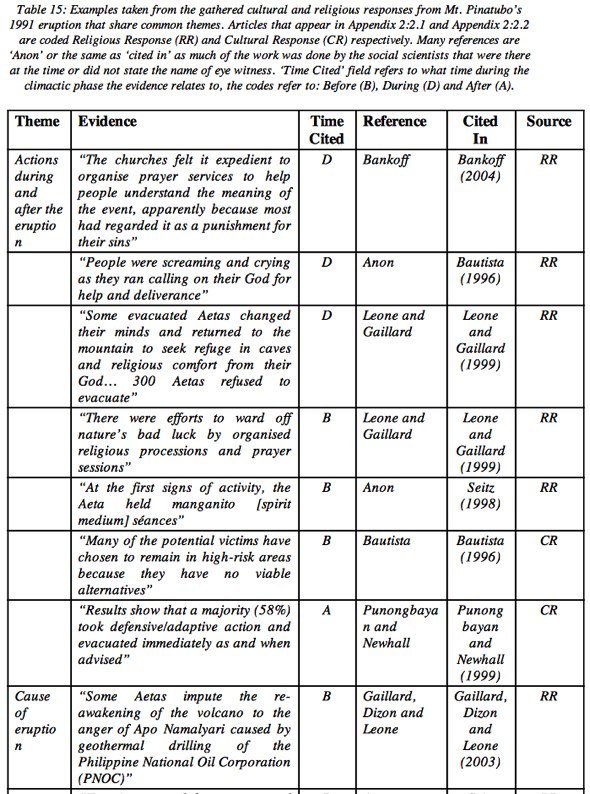

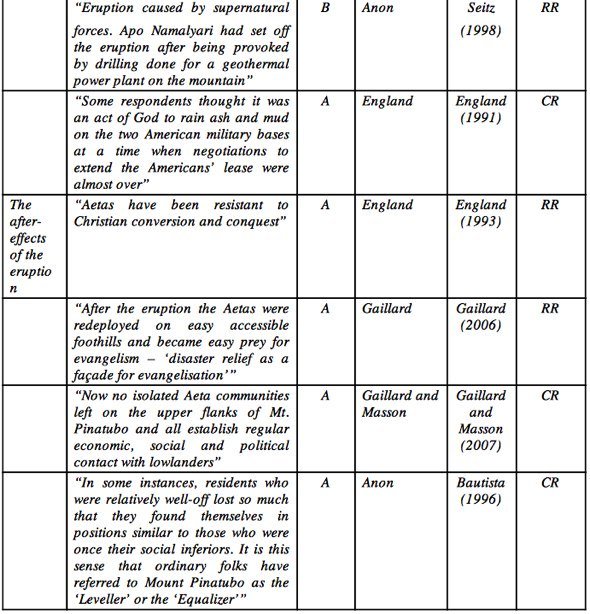

Looking closely at the cultural and religious responses to the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, there were three main trends (table 15):

Table 15 highlights the large variety of actions taken by people (local and foreign) during the Pinatubo crisis. Yet, Leone and Gaillard (1999) and Bautista (1996)’s quotes highlight the undercurrent of the traditional beliefs that still existed around Pinatubo at the time of the eruption, even though it is one of the most Christian nations in South East Asia:

- “Some evacuated Aetas changed their minds and returned to the mountain to seek refuge in caves and religious comfort from their God… 300 Aetas refused to evacuate”

- “There were efforts to ward off nature’s bad luck by organised religious processions and prayer sessions”

Similar to Krakatau’s responses, local beliefs appeared strongly in the ‘cause of the eruption’ section. This response was reduced compared to that of Krakatau as Pinatubo’s unrest period was longer and heavily monitored and the size of the population that was impacted was less than at Krakatau. The responses only mention two causes of the eruption: the link between Apo Namalyari, the god of the volcano (Seitz 1998), and the encroachment that the PNOC caused (England 1991).

The after-effects of Pinatubo’s eruption were very mixed. England (1993) and Gaillard (2006) focused on the evangelist movement in the recovery stage, whereas others focused on the social impact and damage that the eruption caused, such as: Bautista (1996) and Gaillard and Masson (2007).

Table 15 highlights that even in modern day societies the undercurrent of local, syncretic beliefs are still prevalent in disasters and that the influence of cultural and religious responses to disasters are well established. Also another key point to highlight is the importance of author and theme analysis (Sections 4.3.2 and 5.3.1) as this can give a bias towards certain responses. This concept of bias can be a major part for any methodology. It is for this reason that the following sections (Sections 7 and 8) provide a survey which collects 170 responses from a range of scientists to aimed to remove any bias seen from the previous sections.

6 Survey Methodology

The eruption of Pinatubo in 1991 and Krakatau in 1883 gave demonstrations on how important religious and cultural responses can be for people’s motives and actions during an emergency. Understanding these actions, working with the local population and using oral traditions can be seen as a great advantage.

Given that the eruptions of Pinatubo and Krakatau were 129 and 21 years ago, the next step was to analyse how cultural and religious understandings are perceived by scientists currently. A survey was generated and sent to earth and social scientists that work within volcanic research and/or within volcanic risk reduction during an emergency. A survey was chosen over other qualitative methods, such as interviews and short answer questioning as it provided a short response and also had the ability to be sent via the internet and gather a much larger audience.

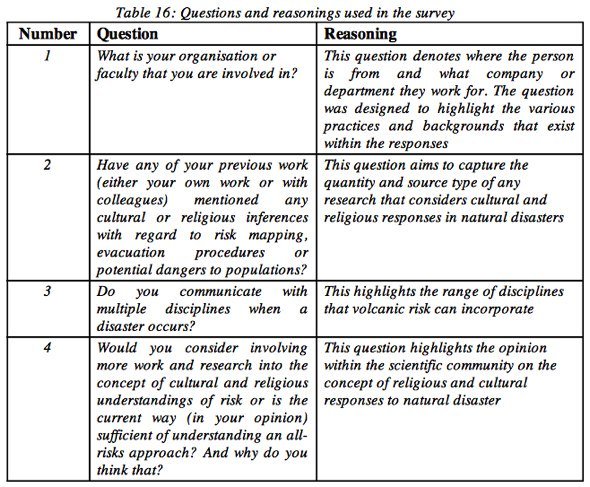

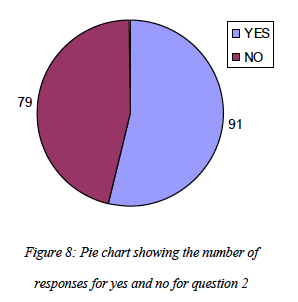

The survey was sent via email through the Volcano ListServ and IAVCEI mailing lists as these mailing lists consist of earth and social scientists that work within the field of volcanology and anthropology. There are currently 420 subscribed members of IAVCEI and around 2,000 active emails subscribed for Volcano ListServ (actual number is unknown as it constantly changing). 170 anonymous responses were gathered; this provided a feedback of 14.2% of potential responders. The questions used in the survey can be seen in table 16.

A blank survey can be seen in Appendix 3: 3.1.

7 Survey Data and Analysis

7.1 Summary of Findings

Although only four questions were asked in the survey, they demonstrate expert views on whether cultural and religious concepts are important in volcanic risk reduction, especially that of question 4 (Table 16). The following sections now individually look at the outcomes of each question.

7.1.1 Results and Analysis for Question 1

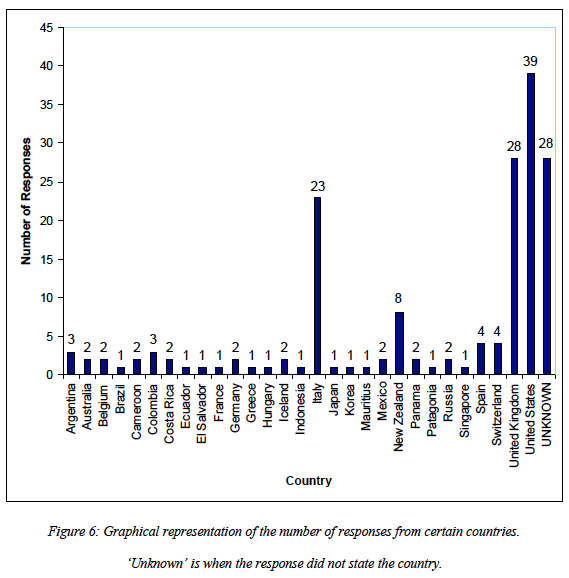

The first question of the survey (table 16) sought to show the number of countries and fields of expertise in the responses. Figure 6 shows the coverage of countries from the responses.

Figure 6 shows that a large number of responses came from Italy (23), the United Kingdom (28) and the United States (39), this could be due to a large proportion of IAVCEI members living in those countries, skewing the data. Also figure 6 highlights that a minimum of 29 countries (excluding ‘unknown’) responded to the survey.

As well as where the responses were from, the next important point is to assess the fields of expertise and educational backgrounds of the responders, as well as what influences they have on volcanic risk reduction (similar to Sections 4.3.2 and 5.3.1), therefore affecting the overall bias of the responses (figure 7).

Figure 7 shows that a large number of responses came from universities: 45 from an Earth or Geo-based Department and 66 from universities of unknown departments. National Institutes count was relatively high compared to the other sections as well (24), dominated mainly by ‘Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia’ from the Italian responses (9 out of 23).

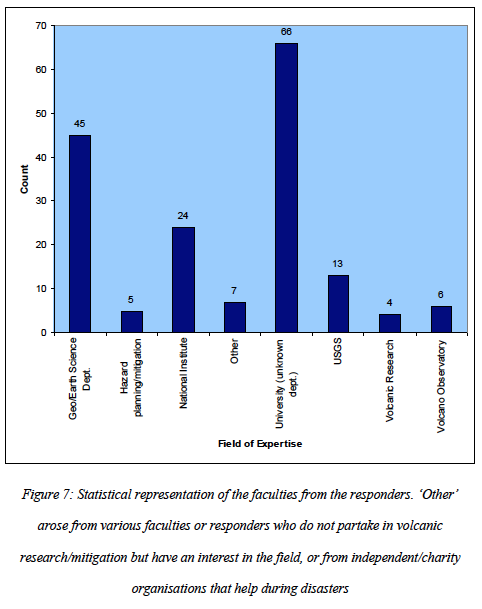

7.1.2 Results and Analysis for Question 2

Question 2 highlights the quantity of work that has either being done or has been completed on the idea that culture and religion play an important role within risk assessment (figure 8).

Although the coverage of fields of expertise was diverse, the split for this question was almost 50/50 (53.5% and 46.5%). This shows that the field of culture and religion within risk mitigation is neither understudied nor over studied. Or that the responses were bias in regard to the Volcano ListServ and IAVCEI mailing lists.

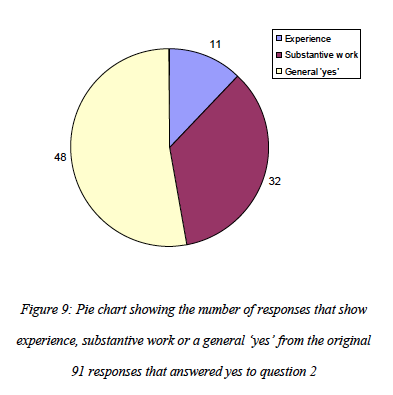

The drawback of this question, however, is that it does not state the quantity of work done. This question asks solely if work has been done, but not to what level. On the other hand some responses stated further work in the answers and so from the 91 responses it can be deduced if the responses either have experience in the field, have done substantive work or answered a general ‘yes’ (figure 9).

Figure 9 shows that 35.2% of the responses have completed substantive work on the subject. However, with 53% answering a general yes, this still creates a void in the study on how much work has been done on the subject.

Linking this back to tables 1, 2, 3 and Section 2 it adds to the idea that the growth of work in this field is increasing, with many social scientists and researchers looking more into understanding why and how people behave during disasters.

7.1.3 Results and Analysis for Question 3

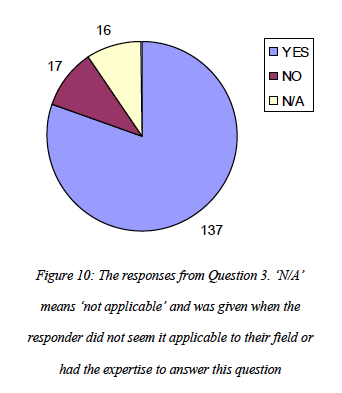

Question 3 was aimed at those mainly who contribute to disaster mitigation and research, for example: the USGS, the national institutes, volcanic research and hazard planning/mitigation (Section 7.1.1) (figure 10).

Figure 10 shows that a large proportion of the responses work in a multi-disciplinary fashion (80.6%), with a small percentage disregarding the idea of a multi-disciplinary approach entirely (10%).

Unfortunately, due to the diverse range of responders not everyone was liable to answer the question, e.g.: “This is not in my area of expertise” (5), and so there is a small percentage that answered ‘not applicable’ (9.4%).

It is clear that studies into risk assessment needs a multidisciplinary approach. As Sections 1 and 2 highlight culture and religion does not exist within one field and so the idea of a multidisciplinary ideal puts the concept into good stead for further research.

7.1.4 Questions and Results to Question 4

Question 4 is split into two parts;

Would you consider involving more work and research into the concept of cultural and religious understandings of risk?

Or is the current way (in your opinion) sufficient of understanding an all-risks approach? And why do you think that?

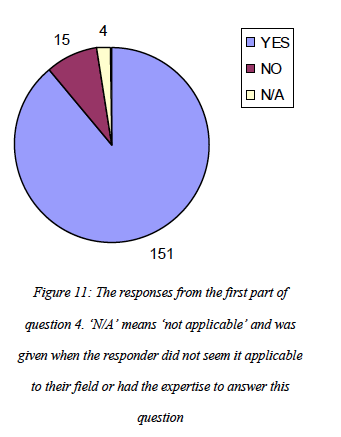

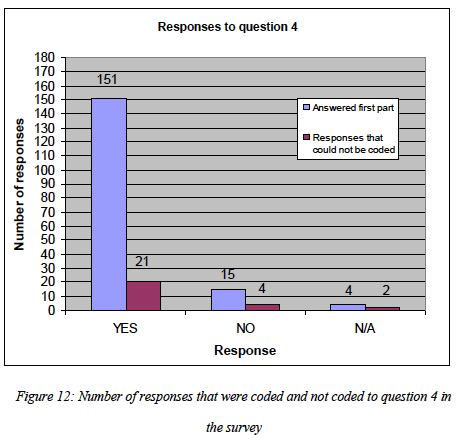

The first part was answered with simple yes or no answers (figure 11). The second part, however, is more subjective, requiring codes to be picked out as it consisted of qualitative research (Section 2.3.2).

Similar to question 3, a large proportion answered yes (88.8%), giving the impression that research in this field is considered important. On the other hand, there is still a small percentage (8.8%) of the responses that believe further work in this field is not necessary.

Linking this with question 3, Sections 1 and 2 and that the majority of physical scientists agree (in this survey) with Hewitt (1997)’s claim that hazards occur at the interface of society and nature indicates that perhaps physical scientists are open to social sciences.

Understanding that multidisciplinary research is key to understanding the concepts of cultural and religious influences within risk mitigation as the effects of an eruption, no matter the location, ripple into the social and the physical sciences.

With 137 (80.6%) of the responders answering yes for question 3 and 151 (88.8%) of the responders answering yes for the first part of question 4, it seems that there are more responders that do not work in a multidisciplinary fashion but would like more work to be done in this field.

This creates two potential thought processes. Firstly, either the difference in responders shows that there is potential to greatly increase the number of researchers in the field of cultural and religious concepts in risk assessment. Or that the responders show that there are currently many people interested in the topic of cultural and religious influences within risk mitigation but have no time to pursue it further or work in a field that can use the information gathered for further research.

This potential divide becomes clearer once the second half of the question is asked. With the potential of opinion and open questioning being asked. For this reason grounded theory was used (Section 2.3.2).

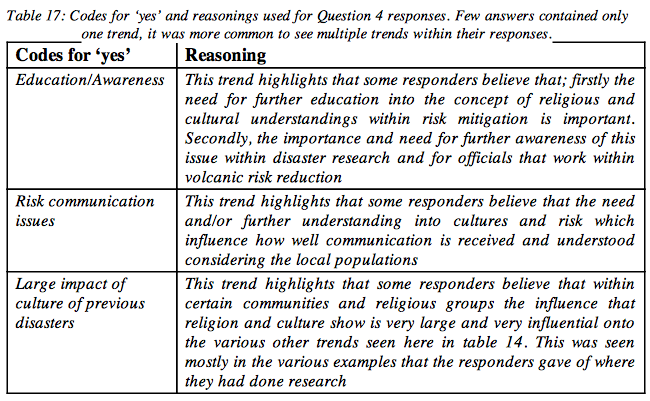

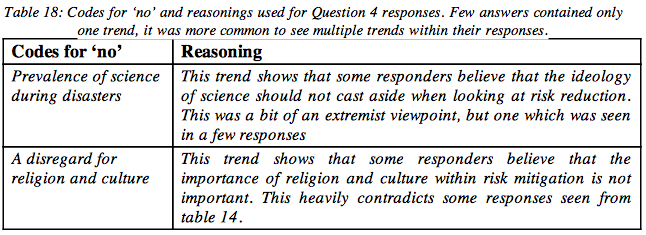

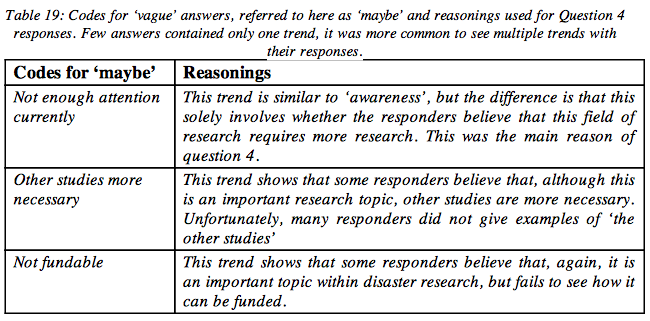

As question 4 consisted of two separate questions the coding approach is split; one set of codes for those responses that answered yes to the first part (table 17), one set of codes for those that answered no for the first part (table 18) and another set of codes for those answers that were vague or can be either yes or no (table 19).

The data can be seen in Appendix 3: 3.2.

To draw upon the codes mentioned in tables 17, 18 and 19, some of the responses given were key turning points in the discussion. Firstly it was evident that education and awareness of cultural and religious research within risk was prevalent in many of the responses (table 17), for example:

- “I think that we have a poor concept of how people actually interact with volcanoes.” (6)

- “Disaster risk reduction cannot be improved without a comprehensive inclusion of cultural understanding into risk reduction efforts” (33)

- “We need more practically focussed research into the role of culture and religion in risk reduction. It is currently under appreciated in academia and in practice. It is what motivates people in times of stress and it can produce seemingly illogical reactions. It is therefore vital to better understand the cultural reactions of people to hazards in order to effectively prepare for the next hazard event” (45)

These highlight how even by interviewing various earth scientists and social scientists who study and research the field of volcanology, the nature of culture and religion is still heavily under researched. This is further proven by looking at the examples that link with the code: “risk communication issues” (table 17):

- “I think more integration with cultural (thus religious) beliefs, understandings and uses are necessary in order to provide better risk mitigation. To me that is very important because otherwise the communication between the different stakeholders does not work properly” (85)

- “Cultural traditions and religion are key factors for understanding how people interpret the natural hazards, especially the volcanic hazards and its related risk. More efforts to investigate their influence in volcanic risk reduction are needed” (131)

- “I think much more work is necessary to increase the effectiveness of our communications with the local populations. We can't communicate well if we don't know what they value, and why they value it” (165)

These above examples highlight how scientists believe that cultural and religious influences can be during a disaster and how vital communication is before, during and after a volcanic disaster with the local communities. This is also prevalent in Section 5.

Another important trend to draw out from the responses is the responder’s views upon how much attention this field of research requires within disaster research;

- “Cultural and religious understanding as well as local myths and traditional songs leads to the understanding of local risk which are associated to the local environment. They are interconnected. More work and research on these aspects provides information which can be helpful in understanding of risks related to volcanic hazard, earthquakes, tsunamis, etc.” (98)

- “Sometimes it might be helpful to have an understanding of the religious beliefs of a given population in order to make a point easier to understand. If such a knowledge of religious beliefs can help to mitigate losses of lives, then it would be worth to expand our horizons to include that type of research” (148)

- “My view is that there is a huge amount of information and ready to use “common sense” knowledge what the western science needs to recognise much better, and in fact utilize and mix with western scientific knowledge. In this process we need to incorporate religious views as well as oral traditions, legends and mythology. There are places where such mixing works well, but in my experiences telling that we are under using this valuable resource” (155)

The notions of more awareness and education, more research within this field and highlighting the importance of “oral traditions, legends and mythology” (155) within risk mitigation has not gone without its drawbacks. There are still several responders who believe this to be a lost cause;

- “Volcanic disasters are a natural phenomenon, and as such are best understood through science. The more people who realize this, the better. Celebrating and/or accommodating people’s various religious/cultural (R/C) views regarding natural disasters seems like a bad idea because, 1) if their R/C views, uninformed by science, are correct (i.e., leads them to make good decisions), then they are correct by mere luck; 2) if their R/C views, uninformed by science, are incorrect (i.e., leads them to make bad decisions), then this could exacerbate the disaster; and 3) it may lead people to think (erroneously) that R/C views can be relevant or important for science. Religious opinions about nature are, at best, neutral with respect to science, and at worst, antithetical to science. Good decisions about how to respond to natural disasters should be informed by the best methods we have for understanding nature – science.” (10)

- “Not really, volcanic disasters you just have to evacuate everyone whatever their race or religion.” (21)

- “No. Religion helps cause many human disasters” (91)

These are a few select responses from the 15 responses that answered ‘no’ to the first part of question 4. To assist the claim that cultural and religious influences are still important I will individual analyse each of these three statements.

The first response assumes that religion and culture has one mind set: “science is bad, and God knows best”. As seen from Sections 1, 2, 4 and 5 this is not the case. Cultures and religions vary throughout the world, existing as polytheistic and syncretic to most societies and religions. The impact which science creates has the idea to work with the societies (if communicated correctly), not against them. The responder’s claim that the values can be “antithetical to science” can sometimes be true in certain areas of the globe, however if this awareness is brought to the attention of local authorities before the time of disaster then the authorities can operate accordingly.

The second response gives a very pragmatic approach, yes it is true, but it does not answer the question which I originally proposed. The question revolved around the idea that cultural and religious influences during or before a disaster can help with risk mitigation. This answer states what everyone should do when a volcano erupts, not what to do prior or how you can use local knowledges for evacuation procedures, for example.

The last response given here again tails away from the main focus of the question. Yes, religion has caused many disasters throughout history but with regards to volcanic disasters, volcanoes are natural disasters not human disasters. For a disaster to occur people must be involved but the source and cause behind natural disasters are usually by no fault of humans.

So far in this thesis, the case studies of Krakatau in 1883 (Section 4) and Pinatubo in 1991 (Section 5) and a survey (Sections 6 and 7) have been discussed individually, the next section of the thesis will bring the three sections together for analysis and highlight any underlying themes that exist throughout the research.

8 Discussion and Inter-comparisons of the Krakatau 1883 Data, the Pinatubo 1991 Data and the Survey

Considering the examples shown in Sections 4, 5, 6 and 7, certain trends are apparent throughout. These may be from the similarities found between Sections 4.3.2 and 5.2.2 due to analysing cultural responses, but there are also similar content analysis methodologies found between the religious responses for the Krakatau and Pinatubo eruptions (Sections 4.3.1 and 5.2.1), e.g. Pray, Spirit and God.

8.1 Critiques of the Survey

However, before full analysis of the survey and its connections to the Krakatau and Pinatubo data commences it is important to understand that the survey does have drawbacks.

Due to the qualitative evidence seen throughout this thesis, no technique can be fully accurate (e.g. Section 4.3.2). This also means that the survey also has disadvantages. The main disadvantages are as follows;

Structure of questions was poor.

- There was no mention in any of the questions that this work was only for volcanic risk mitigation. Even though the survey was attached to an email stating the aim and objectives of the thesis and was sent to volcanic mailing lists (Volcano ListServ and IAVCEI), many responses talked about earthquakes briefly that they had worked on, there by not concentrating fully on the question at hand.

- Question 1 does not state ‘country of origin’, but merely their faculty or organisation, thus creating ‘unknown’ responses. This meant the coverage of the countries covered could have been more spread or covered more countries as a whole.

- Question 4 was split into two. These should have been separate questions, as some responders failed to answer the second half of the question which was the most important aspect of the survey. Figure 12 shows the number of responses that could not be coded due to failure to answer the second part. If this was split into two, further coding and analysis could have been completed.

Further questions could have been asked.

Such as;

- How could you implement the research of culture and religion into volcanic risk mitigation?

- Do you know of any specific examples of volcanic disasters that have heavily noted the influence of cultural and religious during risk mitigation?

These further questions could have changed the coding procedure as well as giving further guidance on how further research could be improved and integrated.

Considering its drawbacks, the survey (Sections 6 and 7) did provide some interesting results. Although some answers were short due to the closed questioning, for example: questions 1, 2 and 3, question 4 provided extra details (Section 7.1.4). The following sections now provide analysis on the connections between the survey questions and responses and the responses gathered from the Krakatau and Pinatubo. Question 1 analysis is omitted as it was only provided to assess the range of fields of expertise and so will not have a link to the responses to the eruptions of Krakatau and Pinatubo.

8.2 Discussion of Question 2 results in light of Krakatau and Pinatubo Data

Although the connection between the answers to question 2 and the eruptions of Pinatubo and Krakatau are somewhat limited, what these responses do show is the impact or awareness of the scientists at the time for cultural and religious issues concerning risk mitigation.

From the responses to the eruption of Krakatau it is evident that concern for cultural and religious values was low. However, as seen from the references throughout Section 4, many of the eye witnesses at the time were not reporting it as a social issue, but more as scientific bewilderment. On the other hand, social scientists are now starting to make connections from the local Indonesian populace and the Dutch populaces actions during the eruption of Krakatau, for example: Simkin and Fiske (1983), Simon (1983), Ellis (2003) and Jablow (2003), showing a shift in the 21st century for this field of research.

With regards to the responses to the eruption of Pinatubo, it is evident that there is progress towards better risk mitigation. There is a much larger research concern with the local populaces and their responses to the eruption, for example: England (1991; 1993), Bautista (1996), Bankoff (2004), Gaillard et al (2005). These show a shift in further research even after the study of Punongbayan and Newhall (1996), further highlighting that research in the field of culture and religion with regards to risk mitigation to volcanic hazards still requires backtracking through past eruptions to understand peoples motives and actions and highlights how understudied this field is.

Linking this with the 91 responses that answered yes to question 2 (Section 7.1.2) it shows that there is a rise in the application of social science, especially in the field of cultural and religious studies to risk mitigation. However, it also shows that there is still a large amount of work still to be done as 46.5% of the responses have never completed research on cultural and religious values.

8.3 Discussion of Question 3 results in light of Krakatau and Pinatubo Data

Question 3 highlighted how earth and social scientists communicate during a volcanic disaster, emphasising the need for multidisciplinary action. As every eruption is different, this is an important topic to consider. The responses were enlightening, showing that 80.6% of the responses work in a multi-disciplinary fashion.

With the regards to the responses of the eruption of Krakatau, however, multidisciplinary risk mitigation (as we view it as present) was not apparent in 1883. On the other hand, the Dutch populaces which escaped the tsunamis and the pyroclastic flows did try and communicate to a variety of people, such as: going to the churches and running to the next town (Van Gestel 1895; Furneaux 1965; Simkin and Fiske 1985). Also the telegraph was used to report the damages. But as far as multidisciplinary risk mitigation, as we see it presently, such as: partnerships, disaster relief programs and policies, nothing existed in Indonesia at the time.

With regards to the Pinatubo eruption, the story was very different. Pinatubo’s risk mitigation plan is one of the famous “success stories” used in volcanic research (Punongbayan and Newhall 1999). As mentioned in Section 5, not only was there a local alert system by PHIVOLCS, but there was also a USGS program that ran parallel to the PHIVOLCS system (Punongbayan and Newhall 1996), making sure that all people in the surrounding area were informed, educated and evacuated on time. The USGS and PHIVOLCS worked with all the local officials of the states surrounding Pinatubo as well as communicating to the indigenous peoples, the military bases, and the lowland communities. As this eruption only occurred 21 years ago, it is possible that some of the responders to the survey (especially the USGS responders) partook in the mitigation program thereby giving first hand opinions of this event. Pinatubo’s mitigation strategy shows clearly that effective risk mitigation strategies can be achieved.

The survey still shows, however, that 10% of responders do not act in a multidisciplinary way. This highlights that there is still further research to complete in regards to persuading and educating scientists the various impacts of volcanic risk and how one field is not enough to cover all the aspects of risk.

8.4 Discussion of Question 4 Results in Light of Krakatau and Pinatubo Data

Question 4 highlighted if the need for adjusting the ‘all-risks’ approach was sufficient or if, in the responder’s opinion, it required further research. This highlighted how large the void of cultural and religious understandings in disaster research is. With 88.8% of the responders replying ‘yes’, it is clear that currently cultural and religious understandings needs more work.

With regards to the responses to the Krakatau eruption, this was largely evident in how the local cultures and populaces responded differently from one another (Section 4.3). Yet 108 years later, during the long eruptive phase of Pinatubo the multidisciplinary strategy vastly improved (Section 5.1). This shows a significant improvement. On the other hand, even though the mitigation strategy at Pinatubo was a ‘success story’ (Punongbayan and Newhall 1999), this process is not repeated throughout the world. The recent eruptive events of Popocatepetl (BBC 2012) and Mount Merapi (Dove 2008; Donovan and Suharyanto 2011) show that cultural and religious practices around volcanoes are still heavily misunderstood.

8.5 Underlying Themes

This section focuses on the underlying themes that run throughout Sections 4, 5, 6 and 7. The reason for doing this is that some important factors could be missed if being constrained by the boundaries of survey questions.

Throughout the thesis there are two important themes that reoccur;

The syncretic relationships between the local beliefs and the orthodox religions (Section 8.5.1)

The impact that culture and religion can have on a populace with regard to their mitigation strategies (Section 8.5.2)

8.5.1 Mixed Populations or Syncretic Relationships?

Throughout Sections 1 and 2, the idea of culture, religion, oral traditions and the idea that societies can exist in multiple mindsets was mentioned, especially in Table 3. It is also evident within the responses of Krakatau’s and Pinatubo’s eruptions (Sections 4 and 5).

In the responses of the Krakatau eruption (Section 4.3) various examples shown in table 9 highlight the mixed populations and syncretic relationships that existed there. Mainly the Islamic faith rituals mixed with the unique beliefs.

Similar syncretic relationships also existed in the responses to the eruption of Pinatubo. However, in the case of Pinatubo, the syncretic relationships are a mixture of Christianity and local beliefs rather than Islam and local beliefs, emphasised in table 15.

The concept of syncretic relationships existing within societies surrounding volcanoes is therefore fundamental to understanding how a society that lives close to a volcano works and reacts during a volcanic disaster.

However, knowing if it is a syncretic relationship or just a mixed audience in both Sections 4 and 5 is still not fully understood. On the other hand, showing that various beliefs exist during a volcanic disaster is one step in the right direction for establishing effective risk mitigation.

8.5.2 Large Impact of Culture and Religion

Considering the responses of the Krakatau and Pinatubo eruptions, it is evident that the impact of culture largely shaped the views, understandings and actions during the eruptions. Sections 4 and 5 as well as Appendices 1 and 2, all highlight the various classifications of the responses to the eruptions, this wide variety of responses shows that culture and religion both play a vital role in volcanic disasters and their mitigation.

Looking at the survey data, one of the codes that was created from the responses was ‘large impact of culture’ (table 17), this also shows that the wide variety of earth and social scientists perceive that culture and religion is an important role in risk mitigation. In fact, 33 responses (18%) emphasised the large impact of culture in the survey.

These two above themes highlight that even though research into volcanic disasters has progressed a long way over the last 2 centuries, there are still comparisons between volcanic disasters that occurred 129 and 21 years ago and to a survey that was completed in 2012.

9 Conclusion

9.1 Results of Study

There are three main points that can be brought forward from this thesis;

With regards to Sections 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 it is clear that not much has changed since Krakatau’s 1883 eruption, religion and culture still play an important role in risk mitigation.

With regards to cultural themes in qualitative data, it is clear due to the nature of ‘culture’ (Sections 1 and 2) methods that involve precise words and phrases (for example content analysis) do not work. In contrast, the importance of specific words and phrases in religious belief means that content analysis is an effective means of investigating religious influences on responses to natural disasters.

The survey results showed that whilst there is wide recognition (nearly 90% of responses) of the importance of religious and cultural influences upon responses to disasters. A much lower proportion of the respondents identified previous cases where such influences had been allowed for in actual volcanic emergencies. This highlights the need for future research in this area.

9.2 Recommendations for the future

This thesis has shown that disaster research and risk mitigation has a void. The void is the amount of research that looks at cultural and religious responses and how they link with volcanic risk mitigation.